You are here

Modeling Technology Supports Glider Rescue

05/03/10 Portland, Ore.

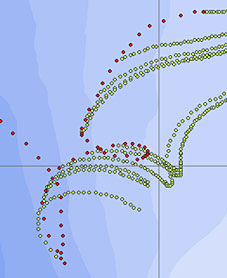

This is an example of the particle tracking model used to predict the direction the glider would drift. Red represents the glider GPS signals. Green represents the particle tracking forecast.Sophisticated forecast modeling tools developed at the Center for Coastal Margin Observation & Prediction (CMOP) were recently used to assist in the rescue of a disabled underwater glider.

This is an example of the particle tracking model used to predict the direction the glider would drift. Red represents the glider GPS signals. Green represents the particle tracking forecast.Sophisticated forecast modeling tools developed at the Center for Coastal Margin Observation & Prediction (CMOP) were recently used to assist in the rescue of a disabled underwater glider.

CMOP researchers spent two days using a particle-tracking model to predict where and when their glider, nicknamed “Phoebe,” would drift ashore. This helped researchers understand how much time they had to stage a recovery operation.

“Once Phoebe became a drifting glider, we treated her as a major piece of scientific instrumentation at risk and an opportunity to test our computer models in a sea emergency,” says António Baptista, director of CMOP. “The forecasting system used for Phoebe is the same that we are currently transferring to the U.S. Coast Guard and NOAA (National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration) for inclusion in their respective operational and emergency response systems.”

Phoebe is a bright yellow glider that moves through the water, gathering information, and sending satellite signals back to land each time she surfaces. The CMOP field team sent her out on the first mission of the year on April 16, 2010 to collect data in the waters off the Washington coast as a collaborative research effort with the Quinault Indian Nation.

Five days into her mission, Phoebe stopped communicating.

Katie Rathmell and Michael Wilkin, members of the CMOP field team in Astoria, Oregon, waited and hoped to receive a signal from her. Hours passed and still no signal. Then almost 24 hours later, Phoebe called home. She had surfaced and transmitted a GPS signal of her current location.

“We reviewed the files she sent and determined that she had gotten stuck at 8.4 meters below the surface and was unable to come up to the surface,” Rathmell says.

The team theorized that Phoebe got tangled in a kelp bed. After a pre-programmed period of time, she jettisoned her emergency ballast weight, which gave her enough buoyancy to escape the entanglement and surface. But having dropped the ballast weight meant she could no longer dive or maneuver. Phoebe was adrift in the ocean.

Rathmell and Wilkin started talking about how to stage a rescue. The challenge was the gale force winds offshore were making the seas too rough for ships to get out of the harbor. The team would have to wait until weather conditions improved.

Even though Phoebe was disabled, she was capable of transmitting a GPS signal every 30 minutes. This allowed the team to track her location. She was drifting south and getting closer to the Columbia River plume. They were concerned she might get caught in the incoming tide. This would pull her into the river and possibly crash her into the jetty. Currents and winds could also push her onto the beach and the surf could break up the glider. The problem was the team was unsure which direction she would drift.

That is when they made the decision to use CMOP’s modeling tools to help narrow down Phoebe’s potential drifting trajectories, possible threats, and windows of time for a recovery operation.

“The team hoped the weather would break in time for a successful recovery. The models helped predict how much time they had to recover Phoebe,” says Paul Turner, senior research programmer.

The data for the particle tracking comes from the forecast models that CMOP runs on a continuous basis. Turner ran simulations for two days using the winds, currents and tides to predict where Phoebe might end up. He generated graphs that predicted drifting directions in one, two, three and four hour intervals.

“Paul Turner did a very good job of getting the modeling and drifter prediction tools working in a fashion that allowed the data to be useful for us,” Wilkin says.

The forecast model showed that time was running out for Phoebe. The prevailing winds and currents were pushing her closer to shore. It was imperative to rescue her soon.

For several days, the conditions were too dangerous to cross the Columbia Bar and get the glider safely aboard a ship. Then around 10:30 on Sunday morning, the research team received word there was a break in the weather and Captain Dan Schenk from Sea Breeze Charters in Ilwaco, Washington would take them out.

Rathmell and Wilkin boarded the “Nauti-Lady” and took a rough ride over the Columbia Bar en route to Phoebe’s last known location.

Finding Phoebe was a challenge. This time of year there are crab traps set out in the ocean and many of their floats are the same color as Phoebe. The team would spot something on the surface of the water that might be Phoebe but it turned out to be something else.

Phoebe was found tangled in kelp and crab lines off the Washington coast. Enlarge imageThen they spotted her tangled up in crab lines and floats. “She was surrounded by kelp, plastic, beer bottles, and all sorts of trash,” Rathmell says . They were successful in getting hold of her, removing the crab lines, and pulling her aboard the ship. The team safely returned Phoebe to shore.

Phoebe was found tangled in kelp and crab lines off the Washington coast. Enlarge imageThen they spotted her tangled up in crab lines and floats. “She was surrounded by kelp, plastic, beer bottles, and all sorts of trash,” Rathmell says . They were successful in getting hold of her, removing the crab lines, and pulling her aboard the ship. The team safely returned Phoebe to shore.

“The successful rescue of Phoebe, under difficult sea conditions, is a credit to the team work among the Astoria field team, boat operators, modelers and programmers,” Baptista says. “CMOP’s oceanographic knowledge, field observations, computer models, and cyber infrastructure all came together to allow people to make the right decisions at the right time.”

CMOP will use the lessons learned from Phoebe’s rescue operation to further improve their scientific and engineering infrastructure.

Written by Jeff Schilling

###

Phoebe and the forecasting system are part of the SATURN collaboratory. Learn more about the SATURN Collaboratory